Things Just Aren’t Like They Used To Be – Are Nissan a Motorsport Failure in the 21st Century?

With over 100 years of innovation and pioneering technology, pushing the boundaries and impressing the world, Nissan has grown to be Japan’s 2nd biggest automotive manufacturer, but at what cost? Today Stelvio Automotive looks into Nissan’s motorsport missteps and asks what’s gone wrong this millennium?

By Sean Smith

The Nissan Group can trace its origins back to the beginning of the 20th century when the “Kaishinsha Motor Car Works” (which would eventually become Datsun), began trading in 1914. The Nissan name itself appeared 14 years later and, as they say, the rest is history. Over the course of the 1900s Nissan would rise, along with Honda and Toyota, to become one of Japan’s big three marques in the country’s booming automotive sector and one of the biggest companies in the world.

Nissan are the biggest member of the ‘Nissan, Renault and Mitsubishi Alliance’, accounting for over half the trio’s total output, which has seen a concerted effort in the development, production and distribution of a well-reviewed line-up of cars across all sectors of the industry. It has also lead to advances in vehicle safety and EV and battery technology which has all contributed to the group becoming the 3rd largest automotive manufacturer in the world.

But... Before ‘the Alliance’s’ inception in 1999, Nissan was world famous for its motorsport heritage, and the question today is, has that particular string to its bow gone limp in the pursuit of boardroom profit margins?

As far as I am aware and, as far as I can search the first page of Google, Nissan have never been in Formula 1 as either an engine supplier, or as a works team. Much like Honda has never shown a great deal of interest in top-tier prototype racing at Le Mans, it appears Nissan are much the same with the so called “pinnacle of motorsport”. Nissan have, however, been involved, in one form or another, in just about every other long-standing motorsport division, from multiple eras of racing at Le Mans, to Formula 3, to every level of GT racing and touring cars ever devised.

Throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s Nissan were a hugely successful marque and won a multitude of trophies and championships across the globe. This included a double victory at the Bathurst 1000 in 1991-2 where the dominant R32 Skyline GTR was adorned with the “Godzilla” name, a car so good it was banned from 1993. But, when you look at modern times, aside from the current GTR winning every other GT3 event it entered at the start of the decade, Nissan have been rather lacklustre with their top-line efforts at motorsport stardom.

Prototypical Nightmares

Let’s start with the big one, the 2015 Nissan GTR LM Nismo LMP1 car. The subject of my first ever published article, the car which came to the party with a claimed 1,200bhp, front wheel drive, venturied aerodynamics, exhausts coming out of the bonnet, odd sized tyres front to back and months of testing at COTA before its Le Mans debut. Without telling every detail again, it was a disaster. In qualifying, one of the three cars failed to beat a Nissan powered LMP2 machine and the best of the three was 15 seconds slower than the pole sitting Porsche. My favourite useless fact on this is that even the time of the fastest GTR LM Nismo was slower than Nissan’s last LMP1 appearance, 16 years earlier, with the R391, by 0.8 seconds. All cars either retired or were unclassified in the race and the project was abandoned, never to be seen again.

Aside, that is, from one part - the engine. The V6 turbo would eventually find its way to the ByKolles team, but even during that partnership (which was discontinued in 2019) the Nissan block was accused of being unreliable with it famously finishing the 2018 Fuji 6hr while running 100bhp down due to a turbo issue. It should be said though that with regards to Le Mans and the WEC, Nissan did produce a great engine for the LMP2 class which, despite being an open formula, was almost exclusively used by every team who raced before the current Gibson block was forced in by the FIA.

Next up, we stay in the same vein of LMP style prototype racing and take a look at Nissan’s DPi programme. The US replacement class to the old ALMS series has seen a healthy revival of prototype racing in the States, however, Nissan have not been at the top of the list when it comes to the successful constructors. The DPi class, now in its sixth season under the current ruleset, has been largely dominated by Cadilac. Nissan, have powered a driver to 5th in the 2017 standings, winning a single race, 9th in 2018, winning two races and 10th 2019, with only a single 4th place to their credit as Acura/Honda and Mazda took the fight to the American giant, with Acura winning the manufacturers title. Nissan were 4th and last.

Defeating Victory?

We then come to the Deltawing and ZEOD projects, I am personally in two minds about how they should be rated. The 2012 Nissan Deltawing, to me, was a success as it proved a concept of achieving high fuel efficiency and speed as the car could often keep up with its old DPi and LMP2 rivals. However, others note that it didn’t finish at Le Mans and, had it been more powerful, it may have been able to target even bigger scalps, so it leaves the question of was the car adventurous enough.

As for the ZEOD, yes, it did achieve its goal of reaching a speed of 300kph (186mph)+ and completing a flying lap under electric power only at the 8.4 mile track. But again, it retired at Le Mans and, while the viewers were transfixed on the hybrid LMP1 battle at the front in 2014, it went largely unnoticed with very little running over the practice sessions and very little coverage when it was ever on track, the only time I remember seeing on screen was when it pulled out of the race at the side of the road.

In Super GT, it must be said that Nissan’s GTR and the Fairlady (350z and 370z) have won many championships. The GTR, in particular, has more championships to its name than any other car and it has replicated its success abroad in GT3 circles and GT1 where it won the 2011 title. However, the same is not true for Nissan’s other “tin top” car, the Nissan Altima.

In 2013, Nissan (along with Mercedes), joined the Australian V8 Supercars Championship, taking the fight to the series’ long-standing acts, Holden and Ford, with Volvo also joining in 2014. What followed was that Volvo would have a driver finish 3rd in the standing in 2016 before leaving, Mercedes would show pace at times but not turn out to be a long term partner and leave the series in 2015 and Nissan... well... let’s just give the facts. The Altima has won three races in its 200+ appearances, Nissan have pulled the plug and from 2020 the car will no longer be on the grid. Yes, they lasted longer than Volvo and Mercedes, but the output, especially with the potential resource Nissan could have used, was pitiful.

A Spark in the Darkness

So, is Nissan a motorsport failure in the 21st Century as this article’s title asked? No. On a world stage, have Nissan been an incredibly disappointing motorsport brand we should expect more from? Absolutely! But it must be said that what saves them, almost exclusively, is the success of the GTR, and the Skylines before it, which have won Nissan multiple trophies at home and abroad, with an honourable mention to the LMP2 engine programme.

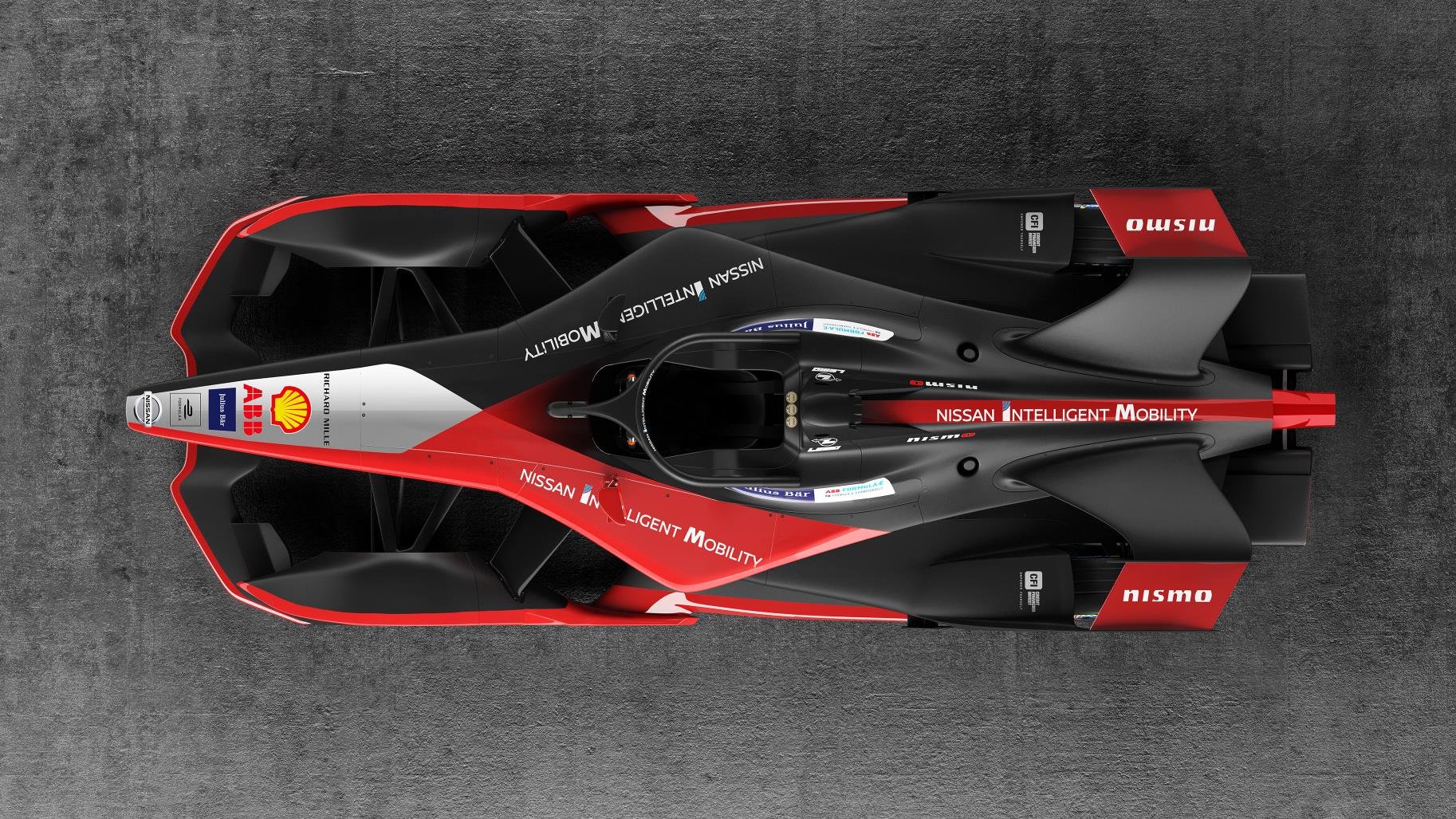

We haven’t even mentioned the near disaster of the 2018/19 Formula E season, or Nissan’s omittance from the BTCC, WTCR, WRC and GTE classes, which count against them further. The problem is, when you look at Nissan’s heritage, it gives you plenty of examples of past glory, from the Calsonic Group C cars to the Primera BTCC entry, the JGTC Skylines and Godzilla in the Bathurst 1000. Nissan’s history books are full of these great examples which fans, including me, love to reminisce about. By comparison, the 21st century cars just aren’t as memorable or, in terms of their winning big events, impressive.

Perhaps because of the boardroom decisions to more actively focus on road car efforts, which have their merits and have produced excellent products, Nissan have slightly dropped the ball. Fans, like me, want to see the Nissan badge at the forefront of the WEC and other international series, we want to see the giant, red Nismo flags and banners, we want to see innovation and forward thinking ideas, such as the Deltawing, or mad new technology which shows the brand off to the world as we were promised with the LM Nismo LMP1, but we’re just not getting it.

Nissan and Nismo have another 80 years left of this century. I have little doubt we’ll see something which shakes the world again in that time, but I hope that happens sooner rather than later as we need more ‘big’ manufacturer involvement across the board.

Maybe they will have something radical for Formula E this year?!?! We’ll wait and see.

Stelvio Automotive – Article 91 - @StelvioAuto